The Teacher of Anatomy...must adapt his mode of instruction to the individual student...some acquire knowledge most readily by description and demonstration, whilst to others a single glance at a diagram or drawing, compared at the same moment with nature, will at once convey the truth.

Robert Knox

My success in life I gratefully attribute to the advantages I enjoyed as one of his assistants...for an ‘eventful period’ of about seven years, during which time I was favoured with much of Dr. Knox’s professional confidence.

Sir William Fergusson, Bart.

The Anatomists and Their Cadavers

Robert Knox, MD, Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, purchased all seventeen of the cadavers sold by Burke and Hare. The first had died of natural causes, but the rest were murdered. His role in the case has always been an enigma. His supporters have argued that it was standard practice on the part of anatomical lecturers to ask no questions about the provenance of their cadavers, because the body-trade was illegal. Moreover, "burking" left no forensic evidence that would point to murder. But Knox's detractors have pointed out that "asking no questions" when confronted with a stiff cadaver dug up from a cemetery was very different from "asking no questions" about such a large number of fresh, uninterred cadavers in the space of a single year. And can we be sure there was no forensic evidence? If Knox was such a great surgeon, shouldn't he have noticed something?

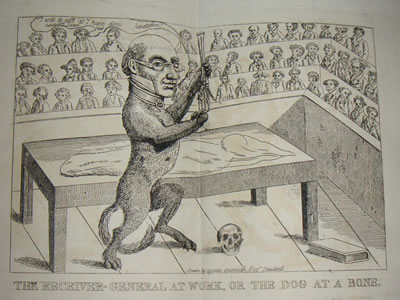

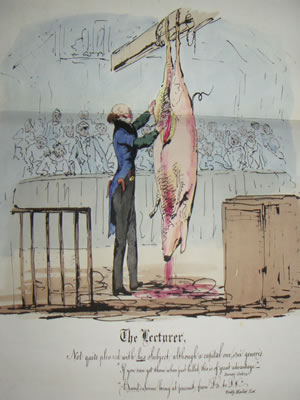

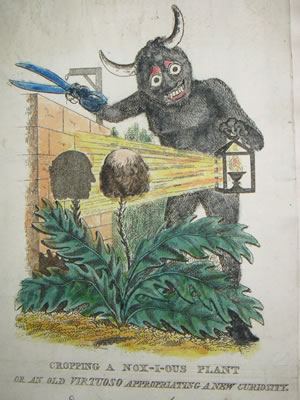

When the news broke concerning the murders in December 1828, Knox was widely assumed to be complicit, though his students and colleagues defended him. He was caricatured for dealing with murders, and likened to a butcher who preferred his meat "fresh." Mindful of the libel laws, the press referred to him with every possible play on "Knox," "noxious," and "obnoxious." Though he taught in Edinburgh for many years after the scandal, his reputation never fully recovered.

We will never know what Knox thought during that fateful academic year of 1827-1828. But we do know that, though formally qualified to practice medicine and surgery, he was not, in fact, a practicing doctor. Instead he devoted all his time and energy to anatomical teaching and research. His goal was eventually to become professor at Edinburgh University, but to succeed he would have to outdo many rivals. He had only been teaching independently for a year before Burke and Hare knocked on his door with their first dead body. It is likely he had already established a network consisting of Edinburgh body-snatchers as well as agents in who sent cadavers from Glasgow, Manchester, and Dublin. Bodies sold by Burke and Hare cost about the same, and were in much better shape.

Knox needed dead bodies not only for students, but also for his ambitious research program in human and comparative anatomy. He had become the Curator of the Museum of the College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, and he was also in the process of seeing several books on anatomy through publication. Since he was so busy, he delegated a part of upkeep of his dissecting establishment at Number 10, Surgeon's Square, to his staff. This included his brother, Frederick John Knox, as the curator of his personal anatomical museum, his technician and doorkeeper, David Paterson, who dealt most directly with purveyors of cadavers like Burke and Hare, and at least three assistants, William Fergusson, Thomas Wharton Jones, and Alexander Miller. All three went on to successful careers in medicine; Fergusson became a prominent professor of surgery in London and was made a baronet in 1866.

Read more about Dr. Robert Knox at the Penn Press Log.

Click on thumbnails to view slideshow.

Images courtesy of the Library of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.